After a recent trip to England, my friend Maureen Tripp brought me back something she knew would be of great interest: a travel book by Charles Dickens, Pictures from Italy. It turns out that Dickens lived in Genoa for more than a year, 1844-45, and traveled extensively around the country, by horse-drawn carriage. He wrote many letters to friends back home, which he later made into a book. Who knew?

It is always hard, for me at least, to read works from another time. My 2025 eyes get in the way. How much do that era’s values and cultural assumptions diminish our appreciation of the work? To what extent should current standards of political correctness apply? Is it fair or even appropriate to let today’s sense of what’s appropriate get in the way?

This question comes up over and over again for me, for while Dickens appreciated Italy enough to live there for more than a year, he describes nearly everything he sees in the most denigrating way possible. He writes that the “young women are not generally pretty, but they walk remarkably well.” Gee, thanks. He describes many of the towns and villages he passes, which he says might look charming from a distance, but “the streets are narrow, dark and dirty, the inhabitants lean and squalid, and the withered old women, with their wiry grey hair twisted up into a knot on the top of the head, like a pad to carry loads on, are so intensely ugly.” Again with the women.

Of his first impressions of Genoa, where he settled and eventually grew to love, he writes, “the unusual smells, the unaccountable filth (though it is reckoned the cleanest of Italian towns), the disorderly jumbling of dirty houses, one upon the roof of another, the passages more squalid and more close than any in St. Giles or old Paris.” Granted, Italy of 1844 was marked by grinding poverty and harsh conditions which ultimately resulted in the great Italian diaspora, with nine million Italians having emigrated to North and South American by World War I. It was certainly not the charming, prosperous place we see today. But even so, I don’t think a country and its people would be described in such disrespectful, insulting terms today, no matter how true.

But here’s another thing about this book that is startling to the modern reader. It turns out that Dickens was in Italy with his wife, sister-in-law, five children, and the family dog! This I learned from the book jacket and Wikipedia — there was not one word of mention of any of them in the entire thing. If this book were written today, we would know about every child’s personalities and idiosyncrasies, any tensions between the wife and her sister, how the dog made out in the carriage all day. Imagine traveling through difficult conditions in a horse-drawn carriage, progressing perhaps only twenty miles in a whole day, no internet, phone or Rick Steves, with none of the kids’ amusements that most of us would have on hand to take them for a 15-minute drive. Even the foods he describes — “cockscombs and sheep kidneys, chopped up with mutton chops and liver, small pieces of some unknown part of the calf, twisted and served up in a great dish like whitebait” — how did that go over with his children? I wish we knew. I’m guessing that the morés of the time were such that that would have been considered private and personal, and perhaps of no interest to others and in bad taste to share. Today (and I say this with the authority of someone who has read countless memoirs about families moving to or traveling through Italy), it would have been the central feature.

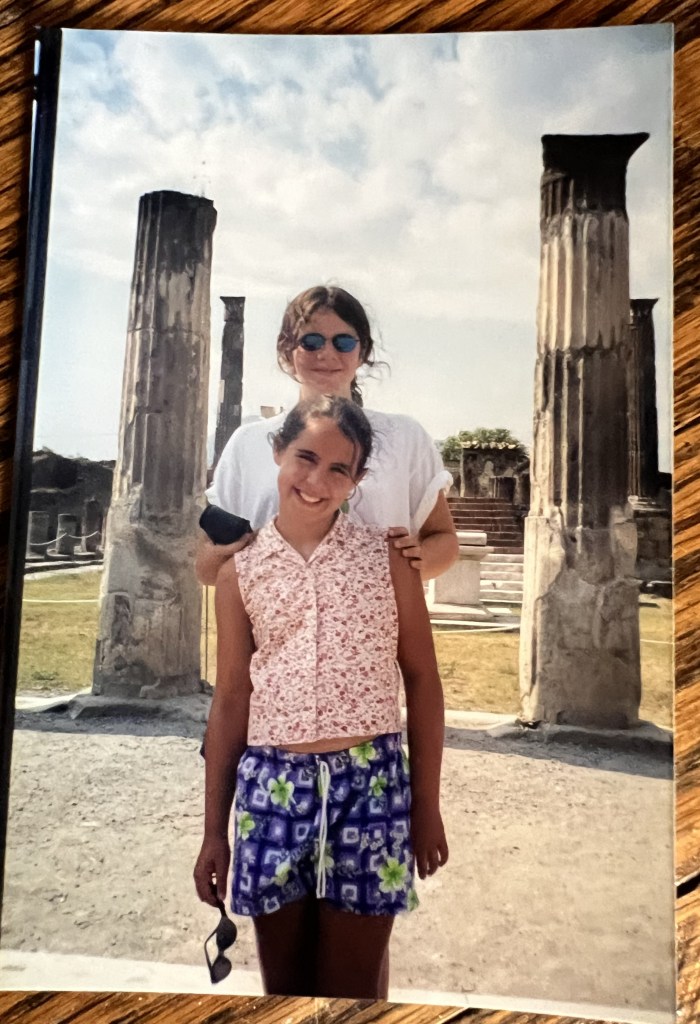

Which brought me to wondering how those Dickens kids ended up. Did they develop a wanderlust for exploring the world, or once they returned to England, did they never want to leave again? My own daughters traveled a lot when they were young and developed a taste for it, albeit without the cockscombs and the mutton and with loads of entertainments for the long journeys. The older one ended up opting to spend half of eighth grade at an international school in London, and the baby is now a travel writer who in the past year alone has been to France, Costa Rica, Italy, Japan and Mexico, and is headed to Tanzania next month.

From what I can tell, the Dickens children did not catch the urge to travel. It seems they led later lives filled with unhappy marriages, failures at business, debt, and illnesses. According to Dickinslit.com, “With only a couple of exceptions, all of the Dickens children led lives of failure and mediocrity.” Was it because they spent a year of their childhoods being cooped up in a carriage and dragged across Italy with a negative, hypercritical father? Was it being forced to eat sheep’s kidneys? We’ll never know.

Gigi…this is a fascinating look at both Dickens and mid-nineteenth century life. And travel. Thanks!

LikeLike