I am fascinated by Fascist architecture.

You don’t have to be an expert to identify them; they are everywhere in Italy and you can’t miss them. Massive, hulking, solid, graceless: they hit you over the head with a comic-book version of strength and masculinity. (I can think of a certain current-day leader who would love presiding over a city of these buildings, except that they lack the gold touches he needs.)

Attending the Italian Open tennis tournament, I had a reason to spend time in a Fascist building complex, the Foro Italico, originally named the Foro Mussolini when it opened in 1932. Benito Mussolini commissioned the complex in the hopes that Rome would be chosen to host the 1940 Olympic Games, showcasing the country and its leader. The arena used for tennis is most notable for these huge, marble statues surrounding the upper perimeter.

Donated by the various Italian provinces, they depict athletes engaged in sporting activities, and were meant to draw a straight line between antiquity and the current greatness of Rome, and of course, the greatness of its leader.

Yesterday, I saw Fascist architecture of a very different sort. We drove two hours into the countryside to tour the Ferramonti International Museum of Memory, on the site of a concentration camp which was in operation from 1940-1943 outside Tarsia, Calabria.

Over its tenure, Ferramonti confined more than 3,800 Jews, as well as political dissidents. Of the Jews, only 141 were Italian; the others were trying to escape the Nazis in Germany and elsewhere. No one was executed at this camp or required to do slave labor; some perished in accidents or from illness, particularly malaria, which was rampant in southern Italy at the time.

The English-speaking guide we had arranged to meet there had a last-minute scheduling conflict, so instead we were sent a guide whose English was just a scratch better than my Italian, so I’m sure I missed a lot. But by her account, as well as according to the books I’ve read on the topic, life for the prisoners was about as benign as one could hope for in a concentration camp, as insane as I feel even writing those words. Families lived together; in fact there were 24 weddings and 21 babies born during the time the camp was operating.

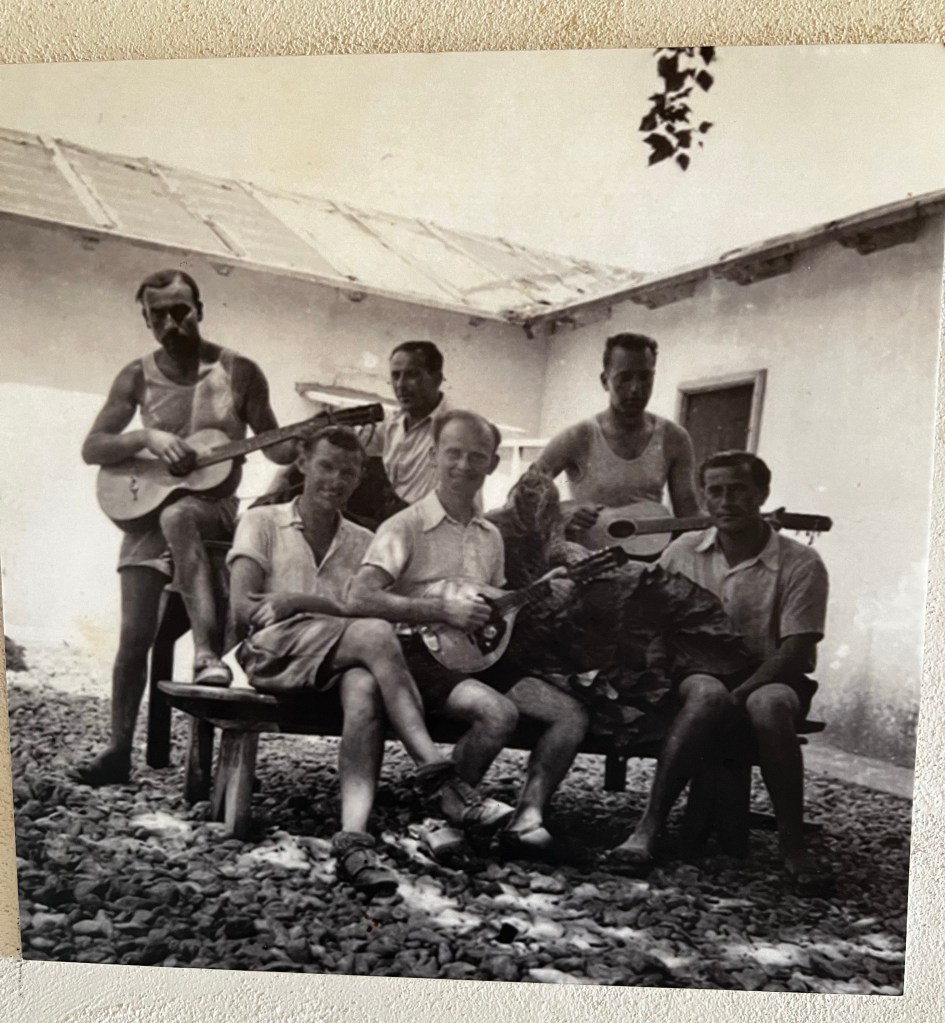

There was a school, sports teams, musical ensembles, and three rabbis to hold regular religious services. Internees with needed skills, such as doctors and dentists, were often released to serve those in neighboring villages. When the camp was liberated by the Allies in 1943, some Jews chose to stay because they felt safer there until the war was over.

Lest one be sanguine about the horrors of being interned in a camp such as this, one glance at the re-created bunk room would quickly disabuse you of the notion that this really wasn’t so bad. But certainly compared to Auschwitz, it was clearly less horrific.

An interesting side note: when I told my cousins in Rome that I would be visiting Ferramonti, they had no idea what I was talking about. These are all educated people, born within a few years of the camp’s existence. I could understand their Italian enough to know that first, they thought I must have been using the wrong words to express myself. Then they agreed it must have been a German camp of some sort. As far as I could tell, this was an entirely Fascist Italian product; perhaps set up to serve their alliance with Hitler, but in no way dictated by him. Our guide was not surprised to hear that my cousins were not aware; this aspect of their history is not widely known by Italians.

So which form of architecture deserves the designation of Fascist? The grand soaring buildings meant to show the majesty of the state, its people, and their glorious leader? Or the rude barracks where nearly 4,000 Jews were confined? I vote for Ferramonti. There could be no better example than those simple buildings of the Fascist impulse to isolate, punish and demean those who are seen as different, threatening, inferior, or generally not with the program. We would do well to pay attention.

Sounds a lot like our Japanese internment camps found legal by none other than that giant of liberalism Justice Douglas.

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike